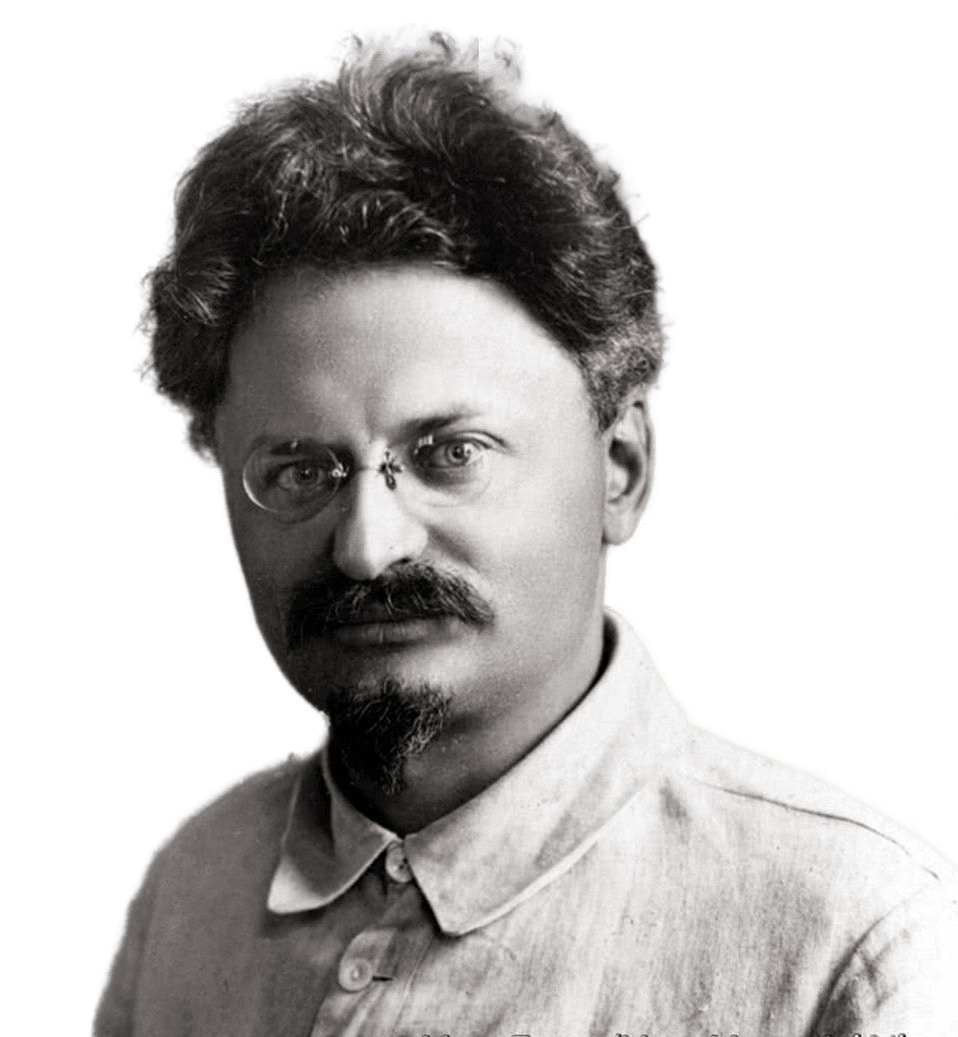

Biography

Birth: October 26 (November 7), 1879, Yanovka, Yelisavetgrad District, Kherson Province, Russian Empire.

Death: August 21, 1940 (age 60), Coyoacán, Mexico.

Party: RSDLP(b)/RKP(b) (1917-1927), SDPS.

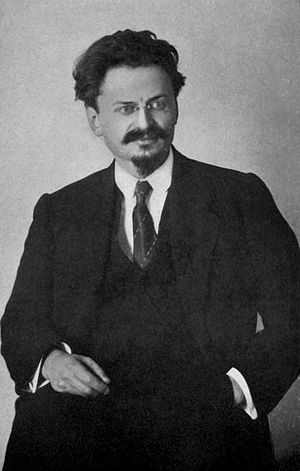

Profession: revolutionary, statesman, writer.

Lev Davidovich Trotsky – Russian revolutionary, active participant in the Russian and international socialist and communist movement, Soviet state, party and military-political figure, founder and ideologist of Trotskyism (one of the currents of Marxism).

Author of works on the history of the revolutionary movement in Russia (“Our Revolution”, “Betrayed Revolution”), the creator of major historical works on the revolution of 1917 (“History of the Russian Revolution”), literary and critical articles (“Literature and Revolution”) and autobiography “My Life” (1930).

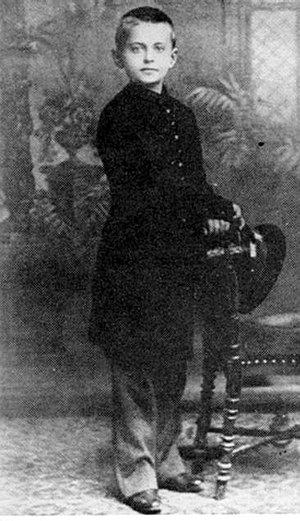

Childhood and Youth

Lev Davidovich Bronstein was born on October 26 (November 7), 1879, the fifth child in the family of David Leontievich (1847-1922) and Anna Lvovna Bronstein (née Zhivotovskaya), rich landlords from the Jewish settlers of the farm near the village of Yanovka, Yelisavetgrad district, Kherson province (now the village of Bereslavka, Bobrinets District, Kirovograd region, Ukraine). The parents came from Poltava province. In his memoirs Trotsky writes that as a child he spoke Ukrainian and Russian, not Yiddish.

On reaching school age he was admitted to St. Paul’s School in Odessa, where he studied from 1889 to 1895. Among his teachers was Anton Mikhailovich Gamov – the father of the famous physicist Georgy Antonovich Gamov. During his school years he lived in Pokrovsky lane, house number 5 of Leiba Triger, a quarter of 1, in the family of his mother’s cousin – Moisey Lipovich (Filippovich) Spentzer (1860-1927) -the future chairman of the partnership of scientific publishing house “Mathesis” and the father of the poetess Vera Inber. He completed his school education in the city of Nikolaev.

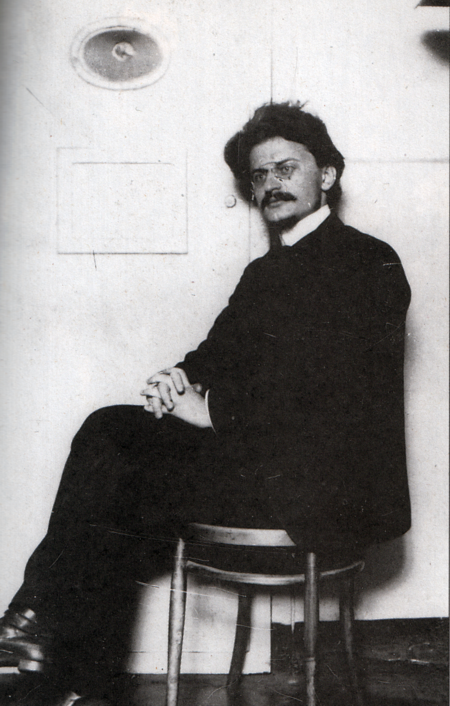

Beginning of revolutionary activity, first exile and emigration

In 1896 in Nikolaev, Lev Bronstein (in the future – Trotsky) participated in a revolutionary circle and conducted propaganda among local workers. In 1897 he took part in the foundation of the Southern Russian Workers’ Union, and on January 28, 1898 – was first arrested by the tsarist authorities. Bronstein spent two years in prison in Odessa, which became the first serious test of his revolutionary resolve. Bronstein fell into depression during his first time in prison and even had thoughts of suicide. But soon his anxiety receded, Bronstein became accustomed to the prison order, and on October 10, 1899 a “relatively mild” verdict in the case of the Southern Russian Workers’ Union was pronounced in the Odessa court: The four main defendants (Bronstein, Alexandra Sokolovskaya and her two brothers) were to be exiled to Eastern Siberia (Irkutsk province) for four years, while the other defendants “got off” with a two-year exile (Sholom Abramov (Grigory Abramovich) Ziv and Shmuil Berkov Gurevich) or even just exile from Nikolaev under the public supervision of the police.

Bronstein’s works, also published in Europe – as well as his public speeches in Irkutsk – attracted the attention of the young revolutionary to the leaders of the RSDLP: in the fall of 1902, he was arranged to escape from Siberia. In Irkutsk, local Marxists gave him an authentic passport form, where he himself entered the name “Trotsky” (after the senior warden of the Odessa prison). Made a stop in Samara, where he met with the head of the “Iskrov Center” Gleb Krzhizhanovsky. He visited Kharkov, Poltava, and Kiev, where he tried to establish connections with the local social-democrats or create appropriate organizations without success. Near Kamenetz-Podolski, with the help of smugglers, he crossed the Hungarian border and traveled by train to Vienna. Then he arrived in Zurich, where he established warm relations with Paul Axelrod. In late fall he reached London, where he had his first meeting with Vladimir Lenin, who had recently published his book What Is to Be Done? Researchers believed that his stay in Siberia and contacts with local revolutionaries were of great importance for the formation of the future Commissar’s political views – for “his party self-determination.”

After arriving in London to see Lenin, Trotsky became a permanent member of the newspaper, gave essays at meetings of emigrants and quickly gained fame. As Trotsky himself recalled: “I came to London as a big hick, and in every sense. Not only abroad, but also in St. Petersburg I had never been before. In Moscow, as in Kiev, I lived only in a transit prison.

The insoluble conflicts in the editorial board of Iskra between the “old men” (G. V. Plekhanov, P. B. Axelrod, V. I. Zasulich) and the “young men” (V. I. Lenin, Yu. O. Martov and A. N. Potresov) prompted Lenin to offer Trotsky as the seventh member of the editorial board, but, supported by all the members of the editorial board, Trotsky was ultimatelly rebuffed by Plekhanov.

At the II Congress of the RSDLP in the summer of 1903, Trotsky supported Lenin so ardently that D. Ryazanov dubbed him the “Leninist cudgel. However, Lenin’s proposed new composition of the editorial board – Plekhanov, Lenin and Martov, with the exclusion of Axelrod and Zasulich – prompted Trotsky to side with the aggrieved minority and be critical of Lenin’s organizational plans.

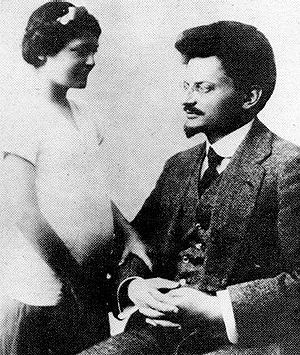

In 1903 Trotsky married Natalia Sedova in Paris (this marriage was not registered, since Trotsky never divorced A.L. Sokolovskaya).

In August 1903, Trotsky attended, as a correspondent of Iskra, the Sixth Zionist Congress held in Basel, chaired by Theodore Herzl. According to Trotsky, this congress demonstrated “the complete decay of Zionism,” in addition, in his article Trotsky mocked Herzl personally.

In 1904, when serious political differences emerged between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks, Trotsky moved away from the Mensheviks and became friendly with A. L. Parvus, who fascinated him with the theory of “permanent revolution. At the same time, like Parvus, he advocated uniting the party on non-factionary positions, believing (in the book “Our Political Tasks”) that the impending revolution would smooth over many contradictions.

In 1904, Trotsky’s pamphlet “Our Political Tasks,” a response to Vladimir Lenin’s “Step Forward, Two Steps Backward,” was published. It is the author’s first relatively major work and was directed against the party split in the RSDLP, which Lenin was accused of. The pamphlet contains both “criticism and

refutation” of Lenin’s ideas and pejorative epithets about the Bolshevik leader, in which Trotsky -considering it necessary to involve workers rather than professional revolutionaries in the revolutionary movement – presented his concept of party “centralism”, different from Lenin’s “substitutionism”. In addition, the author – finding many similarities between Leninist ideas and the principles of the French Jacobins (suspicion, doctrinaireism, intolerance, thirst for power) – warned of the danger of “infecting” the social democratic party with similar qualities, capable of launching a new wave of terror and establishing a “barracks regime” with the goal of “dictatorship over the proletariat.

The book was greeted “with indignation” by Lenin himself, who referred to it as a “brazen lie” and a “perversion of the facts. In Soviet times Trotsky “tried to forget” about this work, but “numerous enemies” constantly reminded him of his authorship of critical texts directed “against the organizational principles of Leninism. A number of researchers used Trotsky’s “convincing” analysis of the RSDLP(b) phenomenon as a basis for criticizing Lenin’s theoretical legacy and his principles of party-building. The book was translated into many languages of the world and repeatedly reprinted. In 1990 in the USSR was published a collection of “To the History of the Russian Revolution,” which contained fragments of the pamphlet.

Participation in the 1905-1907 Revolution, Second Exile and Emigration

At the time of the beginning of the revolutionary events of 1905-1907 (the day of “Bloody Sunday”) Trotsky was in exile in Switzerland. He was the first of the socialist emigrants to arrive in the Russian Empire – from Kiev in late February or early March 1905 he went to St. Petersburg, where he began to defend his slogan about a “Provisional Revolutionary Government,” which was part of his theory of permanent revolution. After the failure of the social-democratic organization in the capital, the revolutionary was forced to flee to Finland.

In the fall, even before the proclamation of the October Manifesto, Trotsky returned to St. Petersburg, where he began to take an active part in the newly created elected body – the St. Petersburg Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, in addition, he was engaged in journalism, working simultaneously in three newspapers: Russkaya Gazeta, Nachalo and Izvestia Soviet. After the arrest of Chairman of the Soviet G. Khrustalev-Nosary, Trotsky joined the new “three-member” leadership of the body and actually headed it. After the publication of the Financial Manifesto, edited by Trotsky, 3 (16) December 1905, the Soviet members were arrested by the authorities of the Russian empire and put on trial. In 1906 at the trial of the St. Petersburg Soviet, which received a wide public response, Trotsky was sentenced to perpetual detention in Siberia with deprivation of all civil rights. On his way to Obdorsk (today – Salekhard) he escaped from Beryozov. Biographers of the revolutionary wrote about the events of 1905 as a “turning point” in the life of one of the future organizers of the October Revolution.

Second Emigration

After 1905, as the revolutionary events in the Russian Empire came to an end, Trotsky’s potential as a politician, organizer, and orator did not “find opportunities for equally brilliant expression. In the next few years, he, like many other emigrants, returned to the journalistic activities he had pursued at the beginning of his career. As in 1905 – in the case of the Russian Gazette and the small publication Beginning – Trotsky became an editor. The revolutionary began publishing Pravda: Rabochaya Gazeta, an illegal, non-factionary social-democratic newspaper intended “for broad worker circles” and published from October 1908 to April 1912, first in Geneva and Lvov and then in Vienna, with Adolf Ioffe leading the international section. Initially the newspaper was the organ of “Spilka” (Ukrainian Social Democratic Union), and in 1910 it briefly became the organ of the Central Committee of the RSDLP (Lev Kamenev was included into its editorial board), but this status was not given officially. Both the Central

Committee and international socialist organizations and individuals took part in financing the publication, the circulation of which amounted to several thousand copies.

The newspaper reflected Trotsky’s “internationalist” views and journalistic style, while it also published two hundred letters of workers from many cities of the Russian Empire. Pravda’s articles covered both the domestic and foreign policies of the Russian authorities, as well as party issues related to the factional struggle in the RSDLP. The style, format, language, and “political message” of the newspaper received considerable support at the beginning of the 20th century. After the newspaper of the same name was launched in St. Petersburg in 1912 at the initiative of Vladimir Lenin, which provoked a sharp controversy due to the use of the same name, the old edition was renamed the Vienna Pravda. – The publication of the Bolshevik Pravda “ended the career” of the Viennese paper. In the Soviet History of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). A Short Course” (1938), the Vienna Pravda was mentioned in the section “The Bolsheviks’ Struggle against Trotskyism.

Balkan Wars

In 1912-1913 Trotsky wrote a series of articles about the Balkan Wars, during which he was in the war zone as a war correspondent for the liberal newspaper Kievskaya Mysl. Trotsky arrived from Vienna in Sofia, which became his main “residence” throughout the first period of the Balkan War, on the day the hostilities began; he began to share his Balkan impressions with his readers on the way. During that period, Trotsky, writing under his old pseudonym Antid Oto, supported the slogan “The Balkans to the Balkan peoples!” and advocated the creation of a single federal state on the entire peninsula, following the example of the United States or Switzerland. He also wrote a series of “heartbreaking” articles on the sufferings of the war foot soldiers and the “war atrocities” described to him by the soldiers and officers on both sides of the conflict. From late November 1912 to the summer of 1913, Trotsky was mainly in Romania, where he once again became friends with H. Rakovsky and entered into another correspondence conflict with a supporter of the ideas of P. Milyukov. While in the Romanian capital on the day of the signing of the Bucharest Peace Treaty, the revolutionary composed a number of extensive essays on the history of the Balkans, their current sociopolitical situation and the future of the region.

Trotsky’s material was included in a collection of articles by foreign journalists about the events of the First Balkan War, which was already published in 1913. Later the revolutionary’s correspondence -hailed as a “classic of anti-war journalism” and an example of “brilliant journalism” in general – came to be seen in Bulgaria itself as an important source of information about the events of the time, which never lost its currency even in the 21st century. Trotsky himself saw the role of the war correspondent as preparation for the revolutionary year of 1917. In Soviet times, Trotsky’s “Balkan” works became part of his collected works – the sixth volume of the collection was called The Balkans and the Balkan War (1926). An English translation of the book appeared only in 1980, and in 1993, due to the outbreak of the Yugoslav wars, Trotsky’s work was republished as an important source on the history of the peninsula.

Trotsky recalled in 1923: “During the few years of my stay in Vienna, I had quite close contact with the Freudians, read their work and even attended their meetings at the time. And at the end of 1924 -beginning of 1925, he wrote a letter to Academician Ivan Pavlov, in which he reported that he had studied psychoanalysis with Z. Freud for eight years.

During the First World War

The First World War, which began on August 1, 1914, suddenly posed “difficult” questions for socialists of all countries and political currents: about the reason for the outbreak of hostilities, about the attitude to the war, about the attitude to the government, about the ways out of the war and so on. All these

questions also confronted Trotsky, who was living in Austria-Hungary at the time: at the same time, after almost a decade of advocating the unification of the socialist movement, he found himself in a “particularly difficult” position – the “deepest disunity” in the ranks of the socialists, which had occurred with the beginning of the war, put an end to his political plans. In the first weeks of the war, Trotsky wondered more about the reaction of the socialists to the war than about the causes of the outbreak of the war itself.

Among the younger generation, Lenin, Trotsky, Luxemburg and Bukharin immediately spoke out against the war with a broad front and denounced the treacherous conformity of the Social-Democratic organizations, which had aligned themselves with their class oppressors in the long-anticipated capitalist slaughter.

In 1914, with the outbreak of hostilities, Trotsky and his family, fearing to be interned by the Austro-Hungarian authorities, fled Vienna to Zurich, Switzerland, where he wrote a pamphlet, War and the International, in which he criticized the West European social democrats for supporting their governments in the war and formulated a slogan for the creation of a “United States of Europe. After that the revolutionary moved to Paris, where he became a war correspondent of the newspaper “Kievskaya Mislia” and began to produce the newspaper “Our Word”, in his articles he repeatedly advocated an end to the war with the subsequent beginning of the socialist revolution and the conclusion of a peace without annexations and contributions. In September 1915, Trotsky, together with V. Lenin and Yu. Martov, participated in the international Zimmerwald Conference. Taking the anti-war position Trotsky in the eyes of the French authorities became “an extremely undesirable element” and was forcibly exiled to Spain.

By breaking with the August Bloc during the world war, Trotsky “took the first and decisive step along the road that would later lead him to the Bolshevik Party. In addition, the revolutionary in 1914, contrary to the position of the majority, predicted that the hostilities of the new war would be protracted and bloody. After the October Revolution of 1917 the experience gained by Trotsky in the role of war correspondent became the basis for his activities as a Soviet commissar-warrior.

The 1917 Revolution and the Civil War

Return to Russia

On March 25, 1917, Trotsky visited the Russian Consulate General, where he noticed “with satisfaction” that there was no longer a portrait of the Russian Tsar on the wall. “After the inevitable procrastination and bickering,” he received the necessary documents to return to Russia the same day – no obstacles were put in his way by the old imperial officials. The U.S. authorities also promptly granted visas for the returnees to leave the country. Apparently, in the general turmoil the British Consulate issued transit documents as well – a decision that would later be disavowed by the London authorities. American authorities may have later regretted the issuance of exit papers to Trotsky: in the following months, the State Department strongly warned the control services of the need for more thorough screening of returning emigrants.

Already on March 27, Trotsky and his family and several other émigrés with whom he had become close in the United States – G. N. Melnichansky, G. I. Chudnovsky (Trotsky’s assistant), Konstantin Romanchenko, Nikita Mukhin and Lev (Leiba) Fishelev – boarded the steamship “Christianiafiord” (“Christiania-Fiord”), heading for Europe – to the Norwegian Bergen (just a few months later, in June 1917, this steamer died near Newfoundland. Before his departure, during a farewell address on American soil – at the Harlem River Park Casino – Lev Davidovich urged the people of the United States to organize and “throw off the damned, rotten, capitalist government.

Halifax Arrest

On the way home, Trotsky was interned by the British authorities in Halifax, Canada: the charge was that the revolutionary had received “German money” with the aim of overthrowing the Provisional Government. The detention, accompanied by violence, resonated both in the Russian press and in the international arena, a British officer, presumably Lieutenant M. Jones).

Trotsky’s release was actively promoted by Vladimir Lenin. In the camp Trotsky successfully continued his propaganda work among German prisoners of war. His detention and subsequent release brought Trotsky closer to the Bolsheviks and resulted in other Socialists returning to Petrograd and Moscow choosing not to end up on British soil.

Arrival in Petrograd

On May 4, 1917, Trotsky arrived in Petrograd. At the Beloostrov station on the border (at that time) with Finland he was met by a delegation from the Social Democratic faction of the “United Internationalists” and the Bolshevik Central Committee. Straight from the Finland Station he went to a meeting of the Petrosoviet, where, in memory of the fact that he had already been Chairman of the Petrosoviet in 1905, he was given a seat with a deliberative vote.

Soon became an informal leader of the “mezhrayontsy”, who took a critical stance toward the Provisional Government. After the failure of the attempted July uprising, he was arrested by the Provisional Government and accused, like many others, of espionage; he was also accused of passing through Germany.

Trotsky played an enormous role in “propagandizing” and switching to the side of the Bolsheviks the soldiers of the rapidly decaying Petrograd garrison. Already from May 1917, almost immediately after his arrival, Trotsky began to pay special attention to the Kronstadt sailors, among whom there were also strong anarchist positions. He chose as a favorite place for his performances the circus “Modern,” closed in January 1917 by the firemen. During the July events, Trotsky personally fought off the then popular Socialist Revolutionary leader and Minister of Agriculture of the Provisional Government, V. M. Chernov (although he was a political opponent of Trotsky) from a crowd that was not controlled by anyone.

In July, at the VI Congress of the RSDLP(b), the “mezhrayontsy” united with the Bolsheviks; Trotsky himself, who at the time was in “Kresty”, which did not allow him to address the congress with the main report – “On the Current Situation” – was elected to the Central Committee. After the failure of the Kornilov Speech in September, Trotsky was released, as were the other Bolsheviks arrested in July.

Activities as Chairman of the Petrosoviet (September-December 1917)

During the “Bolshevization of the Soviets” in September – October 1917, the Bolsheviks won up to 90% of the seats in the Petrosoviet. September 22 (9), 1917 Trotsky was elected chairman of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, which he had led during the 1905 revolution. In 1917 Trotsky was also elected to the Pre-Parliament, became a delegate to the II Congress of Soviets and was elected to the Constituent Assembly.

In the absence of Lenin, who fled to Finland in July, Trotsky took over the role of Bolshevik leader. In the Pre-Parliament Trotsky headed the Bolshevik faction. He characterized the Predparliament as an attempt by “censorious bourgeois elements” to “painlessly transfer Soviet legality to bourgeois-parliamentary legality” and defended the need for the Bolsheviks to boycott this body (in his own words – “stood on the boycott position of non-entry”). Having received a letter from Lenin authorizing the boycott, on October 7 (20) at a meeting of the Pre-Parliament he announced that the Bolshevik faction was leaving the meeting hall.

On October 12, 1917 Trotsky, as chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, formed the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee (VRC), composed mainly of Bolsheviks, as well as the Left SRs. The VRC became the main body preparing for an armed uprising. To divert eyes, the VRC was not formally subordinate to the Central Committee of the RSDLP(b), but directly to the Petrosoviet, and its chairman was appointed a minor figure of the revolution, the Left SR Pavel Lazimir. The main pretext for forming the VRC was a possible German attack on Petrograd, or a repeat of the Kornilov action.

Immediately after its formation, the VRC began to work to win over parts of the Petrograd garrison to its side. Already on October 16, Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet Trotsky ordered to issue the Red Guards with 5,000 rifles.

Between October 21-23, the Bolsheviks hold a series of rallies among the wavering soldiers. On October 22 the VRC announced that the orders of the headquarters of the Petrograd Military District without the approval of the VRC were invalid. At this stage Trotsky’s oratorical skills greatly helped the Bolsheviks to persuade the wavering sections of the garrison to take their side.

After the victory of the uprising in October 1917, the WRK, subordinate to the Petrosoviet until its self-dissolution in December, was in fact the only real force in Petrograd, in the absence of the new state machine which had not yet had time to form. At the disposal of the VRC remained the forces of the Red Guards, revolutionary soldiers and Baltic sailors. November 21, 1917 the VRC formed “commission to combat counterrevolution,” VRC closes with its power a number of newspapers (The Stock Exchange Bulletin, “Kopeyka”, “Novoye Vremya”, “Russian Will”, etc.), organizes the food supply of the city. As early as November 7, Trotsky, on behalf of the VRK, publishes in Izvestia an appeal “Attention of all citizens,” announcing that “The rich classes are resisting the new Soviet government, a government of workers, soldiers and peasants. Their supporters are stopping the work of government and city employees, calling for the cessation of service in the banks, trying to cut off railroad and postal and telegraph services, etc. We warn them – they are playing with fire. We warn the rich classes and their supporters: if they do not stop their sabotage and bring food deliveries to a halt, they themselves will be the first to feel the burden of the situation they have created. The rich classes and their acolytes will be deprived of their right to receive food. All the supplies they have will be requisitioned. The property of the chief culprits will be confiscated.

On December 2, the Petrograd Soviet, chaired by Trotsky, passes a resolution “On Drunkenness and Pogroms,” which creates an emergency commission to combat drunkenness and pogroms, headed by Blagonravov, and places military force at the commission’s disposal. Commissar Blagonravov was instructed to “destroy the liquor stores, clear Petrograd of hooligan gangs, disarm and arrest all those who have disgraced themselves by participating in drunkenness and pogroms”.

Activities as a People’s Commissar (1917-1918)

The II All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies appointed Trotsky as People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs in the first Bolshevik government. As evidenced by the Bolshevik Vladimir Milyutin and Trotsky himself, Trotsky is the author of the term “Narkom” (people’s commissar).

Until December Trotsky combines the functions of the People’s Commissariat with the functions of the chairman of the Petrosoviet; according to his own recollections, “for a long time I never visited this People’s Commissariat, because I sat in the Smolny. December 5, 1917 the Petrograd Commissariat announced the self-dissolution and formed a liquidation commission; December 13, Trotsky passes the chairman of the Petrosoviet Grigory Zinoviev. In practice, this leads to the fact that in October-November 1917, Trotsky rarely appears in the Commissariat and relatively little engaged in its affairs because of the overload of current issues in the Petrosoviet.

The first challenge that Trotsky had to face immediately after taking office was a general boycott (in Soviet historiography – “counter-revolutionary sabotage”) of civil servants of the old Foreign Ministry. Relying on his aide, the sailor Nikolai Markin from Kronstadt, Trotsky gradually overcomes their resistance and began publication of secret treaties of the tsarist government, which was one of the programmatic objectives of the Bolsheviks. Secret treaties of the “old regime” were widely used in the Bolshevik agitation to show the “predatory” and “aggressive” spirit of World War I.

Also, the new power soon faced international diplomatic isolation; Trotsky’s negotiations with foreign ambassadors who were in Petrograd yielded no results. All the Entente powers, and then the neutral states, refused to recognize the legitimacy of the new government and severed diplomatic relations with it.

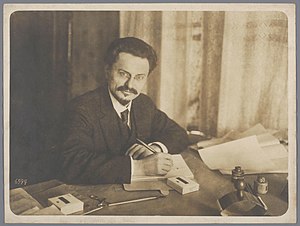

Lev Trotsky, People’s Commissar of Foreign Affairs of the RSFSR, in Brest-Litovsk, 1918

Trotsky’s “intermediate” platform of “no peace, no war: no treaty, we stop the war, and demobilize the army” receives the approval of the majority of the Central Committee, but fails. Germany, after waiting, under the terms of the armistice, for 7 days after the unilateral decision of the Russian side to end peace negotiations, together with Austria-Hungary goes on the offensive, February 18, 1918. The former Imperial Russian Army by this time finally ceased to exist and it proves unable to prevent the Germans in any way. Recognizing the failure of his policy, Trotsky resigned from the post of People’s Commissar on February 22.

In the face of the German offensive, Lenin demands that the Central Committee accept the German conditions, threatening otherwise with his resignation, which effectively meant splitting the party. Also under pressure from the “Left Communists,” Lenin puts forward a new “interim” platform, presenting the Brest Peace as a “respite” before a future “revolutionary war. Under the influence of the threat of Lenin’s resignation, Trotsky, although previously opposed to signing the peace on German terms, changes his position and supports Lenin. At the historic vote of the Central Committee of the RSDLP (b) on February 23 (March 10), 1918, Trotsky, along with four of his supporters abstained, which provided Lenin a majority of votes.

Activities of the Revolutionary Military Council in 1918-1919

Soon after his resignation from the post of People’s Commissar, Trotsky receives a new appointment. On March 14 he received the post of Commissar for Military Affairs, on March 28 – Chairman of the Supreme Military Council, in April – People’s Commissar of Maritime Affairs, and on September 6 -Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the RSFSR.

By February 1918 the former tsarist army had already effectively ceased to exist under the influence of the corrupting propaganda of revolutionary forces, including the Bolsheviks, finding itself unable in any way to delay the German offensive as a result of the efforts of anti-state forces. As early as January 1918 the formation of the Red Army began, but, as Richard Pipes points out, up to the summer of 1918 the Red Army existed for the most part on paper. The then existing principles of voluntary recruitment and election of commanders led to its small number, weak controllability, low combat readiness (“partisanship”).

The main impetus for the Bolsheviks to proceed to the formation of a mass regular army was the performance of the Czechoslovak Corps. The Czechoslovak Legionnaires’ force was only about 40,000-50,000 men, which seemed insignificant for Russia, which a year before had an army of almost 15

million men. However, at that time the Czechoslovaks were almost the only military force in the country that remained combat-ready.

Receiving a new assignment in such circumstances, Trotsky becomes in fact the first commander-in-chief of the Red Army and one of its key founders. Trotsky’s contemporary Dr. G. A. Ziv stated that as a People’s Commissar Trotsky “felt his real profession: … relentless logic (which took the form of military discipline), iron determination and unyielding will, which did not stop before any considerations of humanity, insatiable ambition and unmeasured self-confidence, a specific oratorical art.”

In August 1918 Trotsky forms a carefully organized “Predevoensoviet train,” in which, from that moment, he essentially lives for two and a half years, continuously traveling around the Civil War fronts. As the “military leader” of Bolshevism, Trotsky displays unquestionable propaganda abilities, personal courage and sheer brutality. Arriving on August 10, 1918 at the station of Sviyazhsk, Trotsky personally leads the fight for Kazan. By the most draconian means he imposes among the Red Army discipline, resorting, among other things, to the shooting of every tenth soldier of the 2nd Petrograd Regiment, fleeing at will from their combat positions.

As the Predevoensoviet, Trotsky consistently promotes the widespread use of “military specialists” in the Red Army, for the control of whom he introduces a system of political commissars and a system of hostage-taking. Convinced that the army, built on the principles of universal equality and voluntarism, proved ineffective, Trotsky supported its gradual reorganization in accordance with more traditional principles – the introduction of universal conscription, strengthening the discipline, abolishing the election of commanders, the gradual restoration of mobilization and one-man command, the return of uniforms with insignia, a positive attitude to military greetings and parades.

Trotsky repeatedly is personally on the front line, in August 1918 his train was almost captured by the White Guards, and later that month he almost died on the destroyer of the Volga River Flotilla. Several times Trotsky, risking his life, makes speeches even in front of deserters. At the same time, the tumultuous activity of the Predrevoyensoviet, who was constantly wandering on the fronts, began to increasingly irritate a number of his subordinates, leading to a lot of loud personal quarrels. The most significant of them was Trotsky’s personal conflict with Stalin and Voroshilov during the defense of Tsaritsyn in 1918. According to a contemporary of the events Lieberman S. I., although Stalin’s actions then violated the requirements of military and party discipline, which was condemned by the Central Committee, most Communist leaders disliked Trotsky’s “upstart” and supported Stalin in this conflict.

Murder

In May 1940 there was an unsuccessful attempt on Trotsky’s life. The assassination attempt was led by NKVD secret agent Grigulevich. A group of raiders was led by a Mexican artist and stalinist Stalinist Siqueiros. Breaking into the room where Trotsky was, the assailants inadvertently shot all the bullets and hastily disappeared. Trotsky, who managed to hide behind the bed with his wife and grandson, was not hurt. According to the recollections of Siqueiros, the failure was due to the fact that the members of his group were inexperienced and very nervous. At the inquest, however, he claimed that the action was not originally intended to kill Trotsky, but pursued only two goals: to steal documents discrediting Trotsky, in particular evidence of receiving funds from ultra-reactionary newspapers in the United States, and to force him to leave Mexico.

Early in the morning of August 20, 1940, Ramon Mercader, a NKVD agent, who had earlier penetrated into Lev Davidovich’s entourage as his staunch adherent, came to Trotsky to show him his manuscript. Trotsky sat down to read it, and at that moment Mercader struck him on the head with an ice-axe, which he had carried under his cloak. The blow was struck from behind and from above on the seated

Trotsky. The wound in a skull reached 7 centimeters in depth, but Trotsky lived almost twenty-four hours after the wound and died on August 21. After cremation he was buried in the backyard of a house in Coyoacán, Mexico.

A few days later, on August 24, the newspaper Pravda published an obituary, “Death of an International Spy,” without mentioning the author. The obituary said: “A man has gone to his grave whose name is spoken with contempt and curse by workers all over the world, a man who for many years had fought against the cause of the working class and its vanguard, the Bolshevik Party. The ruling classes of capitalist countries have lost their faithful servant. The foreign intelligence services have lost a long-standing, mature agent, who did not disdain any means to achieve his counter-revolutionary aims.

The Soviets publicly denied any involvement in the murder of Leonid Trotsky. D. Trotsky. His murderer, Ramon Mercader, sent by the NKVD, was sentenced by a Mexican court to the maximum penalty of twenty years’ imprisonment. Released from prison in 1960, Mercader came to the USSR, where he was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union and the Order of Lenin.

Memory

Trotsky’s tenure as Pre-Revolutionary Soviets and People’s Commissars coincided with the formation of a new state, military and propaganda machine, of which Trotsky himself was one of the founders. An integral part of the propaganda system built by the Bolsheviks was the glorification of honored revolutionary figures, their election to the “honorary presidiums” of various conventions and meetings (from Party congresses to school assemblies), the awarding of all kinds of honorary titles (“honorary miner”, “honorary metallurgist”, “honorary Red Army soldier”, etc.), and the renaming of the “honorary miner”. etc.), renaming towns, displaying portraits, and publishing romanticized biographies.

One form of glorification of honored revolutionary figures in early Soviet propaganda was “chieftainism,” which emerged as such even before October 1917. Ataman Kaledin called himself “leader of the army” in August 1917, and one of the obvious manifestations of “leaderism” was a pronounced cult of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, popular among the soldiers, which had spread at least since 1915. In Soviet propaganda, however, Lenin was usually referred to as “the leader of the revolution” and Trotsky as “the leader of the Red Army. During the Civil War Trotsky’s name was given to two armored trains, number 12 named Trotsky and number 89 named Trotsky. Such names were quite common; the Red Army also had, for example, armored train No. 10 named after Rosa Luxemburg, No. 44 named after Volodarsky, or No. 41 “Glorious Leader of the Red Army Yegorov.”

Since at least 1919, it has become traditional to elect “Lenin and Trotsky” to the so-called “honorary presidiums. Thus, on November 4, 1923, Lenin, Trotsky and Rykov were elected to the honorary presidium of the “Red Rubber” plant. In August 1924 Rykov and Trotsky (mentioned in this order) were elected to the honorary presidium of the I All-Union Chess and Checkers’ Congress. In his memoirs Trotsky mentions other examples: back in November 1919, the II All-Russian Congress of the Muslim Communist Peoples of the East elects Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev and Stalin as its honorary members; in April 1920 the same composition was elected an honorary presidium of the I All-Russian Congress of the Chuvash Communist Sections.

The total number of such “honorary presidia” is incalculable, as is the number of different kinds of honorary titles. Lenin was elected “honorary Red Army” in a total of about twenty different military units, the last time just before his death. Trotsky was also elected “honorary Red Army” and even “honorary Komsomol”. In April 1923 a meeting of workers of the Lenin factory in Glukhov decided to appoint Trotsky an honorary spinner for the seventh grade, and a representative of the factory Andreev, speaking at the XII Congress of the RCP(b), said that “And one more order I must tell you from our

In 1923, as a sign of Trotsky’s services to Bolshevism during the struggle against the forces of Kerensky-Krasnov in 1917 and during the defense of Petrograd in 1919, Gatchina was renamed the city of Trotsk, and 5 November 1923 the City Council even elected Lenin, Trotsky and Zinoviev as its “honorary chairmen”.

In fact, by the end of the Civil War, the “cult of Trotsky” was formed as an honored figure of the revolution and the Civil War. Its peculiarity in comparison with the later “personality cult of Stalin” was that the “cult of Trotsky” existed in parallel with a number of other “cults” comparable in size: the personality cult of Lenin, the cult of the “Leningrad leader” and “leader of the Komintern” Zinoviev, the cults of Krupskaya, Tomsky, Rykov, Kosior, Kalinin, the cults of several Civil War military leaders (Tukhachevsky, Frunze, Voroshilov, Budyonny), etc. etc. up to the more minor cult of the famous poet Demian Bedny, in honor of whom Spassk was renamed in 1925. Researcher Sergei Firsov considers the Bolshevik cults of revolutionary figures to be an “inverted” version of the Christian cult of saints. According to Firsov, after Trotsky was expelled from the Party in 1927 and expelled from the USSR in 1929, the process of his “desacralization,” which can be traced in the biographical information in the notes to the collected works of Lenin, began. In 1929 they describe Trotsky as “exiled from the USSR,” in 1930 as a “social-democrat,” and in 1935 his “social-democratic”-“Trotskyism” is already described as “the vanguard of the counter-revolutionary bourgeoisie.” Beginning in 1938, Trotsky is described as a universal villain, the fiend of “bourgeois-fascist” hell, the demon of the world communist system. In the official Soviet literature of the Stalinist and post-Stalinist period (up to Perestroika), Trotsky was accused of many and many “deadly sins. For example, he was accused of surrendering vast territories of the European part of the former Russian Empire to the Germans and Austrians because he disrupted the Brest negotiations, of developing “a traitorous plan to defeat Denikin, rejected at the suggestion of Comrade Stalin.

Order of the Red Banner in commemoration of services to the world proletarian revolution and the workers’ and peasants’ army, and specifically – for the defense of Petrograd – the decision of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviet of Workers’, Peasants’, Cossack and Red Army Deputies on November 7, 1919.