10.01.2023

We were going down the Lena River. The current was slowly carrying several barges with prisoners and convoy.

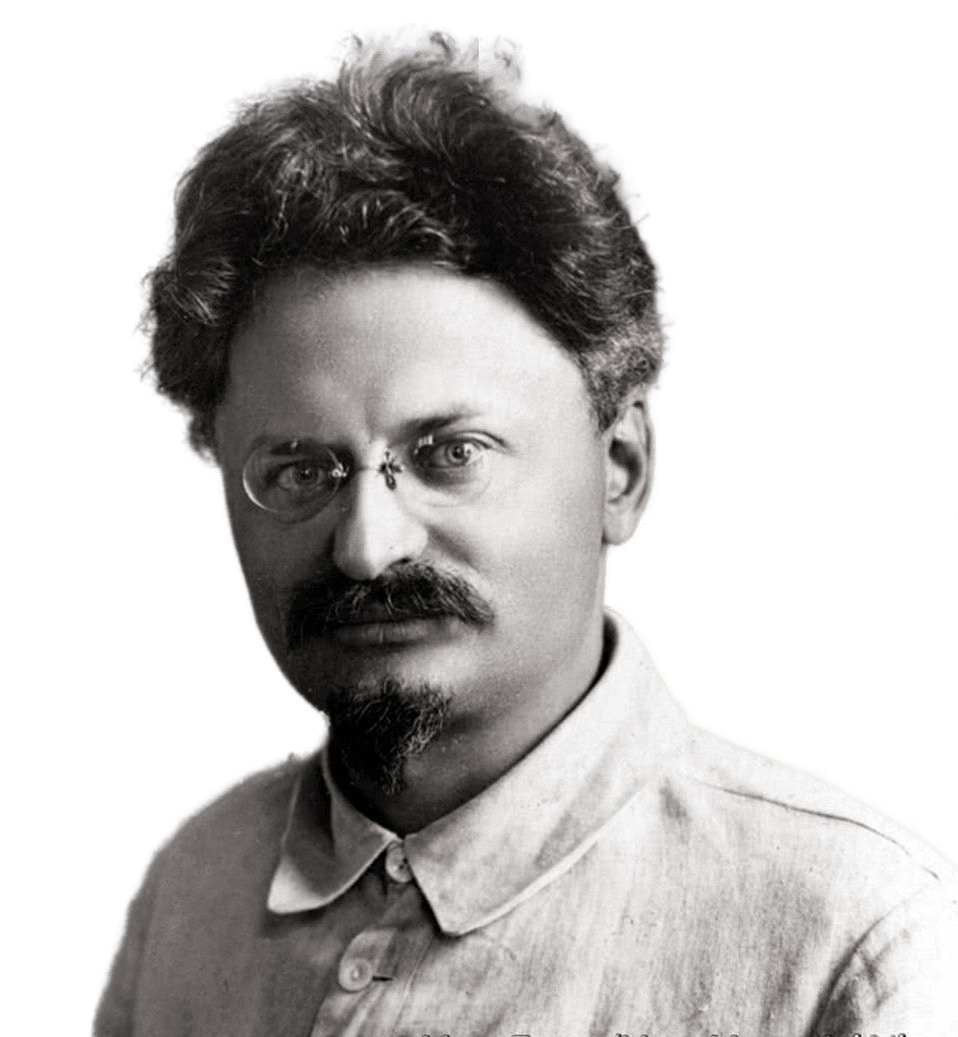

It was cold at night, and the coats we used to cover ourselves with turned to hoarfrost in the morning. On the way, one or two of us were put off in pre-designated villages. We sailed to Ust-Kut village, I remember, about three weeks. Here I was disembarked me along with an exile close to me on the Nikolaev case. Alexandra Lvovna was one of the first in the Southern Russian Workers’ Union. Her deep devotion to socialism and the total absence of everything personal her unquestionable moral authority. Working together work has bound us closely together. So as not to be settled we were married in a prison in Moscow.

There were about a hundred huts in the village. We settled in the last one. There was a forest all around, and a river below. Farther north on the Lena there were gold mines. The glow of gold played all over Lena. Ust-Kut has known better times, with rampant robbery, looting, and racketeering. But in our time the village has calmed down. Drunkenness, however, has remained. The master and mistress of our hut drank themselves intoxicated. Life is dark, deaf, in a far away from the world. Cockroaches filled the hut at night with an alarming rustle, crawling on the table, on the bed, on the face. From time to time we had to move out for a day or two and open the door wide in the 30-degree frost.

In the summer the mosquitoes plagued us. They ate a cow to death, that got lost in the woods. The peasants wore nets on their faces made of horsehair smeared with tar. In spring and autumn. the village was drowned in mud. But the nature was beautiful. But I was cold to it in those years. It was kind of a pity for me to waste my attention and time on nature. I lived between the forests and rivers, almost without noticing them. Books and personal relationships consumed me. I studied Marx, driving the cockroaches off from his pages.

Soon after my arrival in Ust-Kut, I began to collaborate in It was a legal provincial organ, created by the old. It was a legal provincial organ, founded by the old exiled Narodniks, but occasionally seized upon by the Marxists. I began with country correspondences, waited in excitement for the first of them to appear, was supported by the editorial board, moved on to literary criticism and publicism. To find a pseudonym, I opened at random. To find a pseudonym, I opened at random an Italian dictionary – the word antidoto came up, and for many years I signed my articles A n t i d O t o, explaining to my friends, as a joke, that I wanted to introduce a Marxist antidote to the legal press. The newspaper unexpectedly.

The newspaper raised my fee from two kopecks to four kopecks per line. This was the ultimate expression of success . I wrote about the peasantry, about the Russian classics, about Ibsen, Hauptmann and Nietzsche, Maupassant and Estonier, Leonid Andreev and Gorky. I sat up nights scribbling my manuscripts to the back and forth, looking for the right idea or the missing word. I was becoming a writer.

From 1896, when I was trying to repel revolutionary ideas, and from 1997, when I was already doing revolutionary work, but still repulsed by the theory of Marxism, I had come a fair part of the way. By the time I was exiled, Marxism had definitively become for me the basis of my world view and a method of thinking. Now, in exile, I tried to approach the so-called “eternal” questions of human life from the angle I had learned: love, death, friendship, optimism, pessimism, etc. In different.

At different times and in different social environments, a person loves, hates and hopes differently. As a tree feeds its flowers and fruits through its roots with the juices of the soil, so a person finds nourishment for his feelings and thoughts, even if it is the most even the most “lofty,” in the economic foundation of society.