10.01.2023

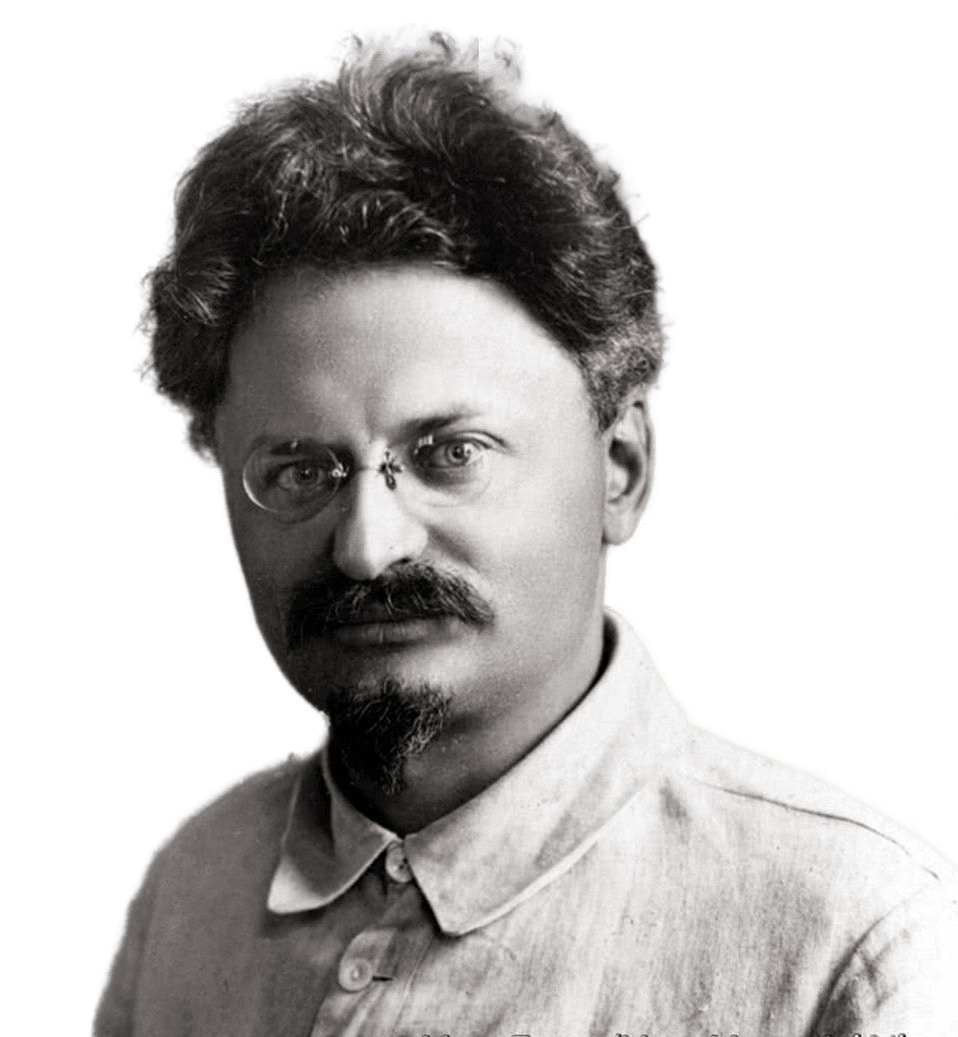

The father was undoubtedly superior to the mother in both intelligence and temperament. He was deeper, more reserved, more tactful. He had an unusually good eye, not only for things, but also on people.

My parents bought very little at all, especially in the. My parents bought very little in general, especially in the old days.

My father knew unmistakably what he was buying. Cloth, a hat, shoes, a horse or a car – he had a sense of quality in everything. I don’t like pennies,” he told me later, as if to say that he was stingy, “but I don’t. I don’t like it when I don’t have it. Trouble is, when pennies are scarce. He spoke incorrectly, in a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian, with a predominance of Ukrainian. People he judged people by their manners, by their faces, by their manner, and he judged them well.

After much work and toil, my mother at one time began. After a lot of work, my mother became ill and went to see a professor in Kharkov. These trips were big events, and it took a long time to prepare for them. Mother stocked up on money, jars of asl, a sack with breadcrumbs, fried chickens, etc.

There were big expenses ahead. The professor had to the professor was to be paid three rubles per visit. This was said. This was mentioned to one another and to the guests, with a raised finger and a peculiarly grave expression on their faces.

There was respect for science, and complaint that it was so expensive, and pride that it was possible to pay such unheard of money. Mother’s return was awaited with excitement. Mother would arrive in her new dress, which in the Janov’s dining room seemed unheard of.

When the children were young, the father was gentler in his interactions with them. Was softer and more even-tempered. The mother was often irritated, sometimes without. The mother was often irritated, sometimes for no reason, just to take it out on the children when they were tired or when they failed in their chores. In those years it was considered more advantageous to ask the father for anything. But as the years passed, the father grew tougher. The reason was the hardships of life, the hassle that grew with the growth of the business, especially in the agrarian crisis of the 1980s, and the frustrations brought on by the children.

In the long winters, when the steppe snow was blowing Yanivka from all sides, piling drifts above windows, my mother loved to read. She would sit on the small triangular couch in the dining room, putting her feet on the chair, or, when the early winter dusk approached, she would sit down in her father’s in her father’s armchair, to the little frosted window, and in a loud whisper she would read a worn-out novel from the Bobrinets’ library, tracing the lines with her weary finger. She was stumbling over the words and stumbling over the complicatedly constructed phrases. Sometimes a hint from one of the children of the children illuminated the reading in a different way in her eyes. But she read persistently, tirelessly, and in her spare.

It was possible to hear her measured whispering in the hall in the free hours of quiet winter days. My father had already learned to read in the folds when he was an old man, to be able to read at least the back of my of my books. I watched him with excitement in 1910 in Berlin, when he insistently sought to understand my book on German Social Democracy.

His father was a very well-to-do man during the October Revolution. His mother died as early as 1910, but his father lived to the power of the Soviets. In the midst of the civil war, which particularly raging in the south, with constant changes of power.

Change of government, the seventy-five year old man had to walk hundreds of kilometers to find temporary shelter in Odessa. The crusaders were dangerous to him. dangerous to him as a large proprietor. The Whites pursued him like my father. After the cleansing of the south by the Soviets, he was allowed to arrive in Moscow. The October Revolution took from him, of course, everything he had he had gained. For more than a year he ran a small state-owned mill near Moscow. He was fond of talking to him.

The then People’s Commissar for Food, Tsyurupa. My father died in the spring of 1922 of typhoid fever. My father died of typhoid fever in the spring of 1922, the same hour when I was making a speech at the Fourth Congress of the Comintern.