10.01.2023

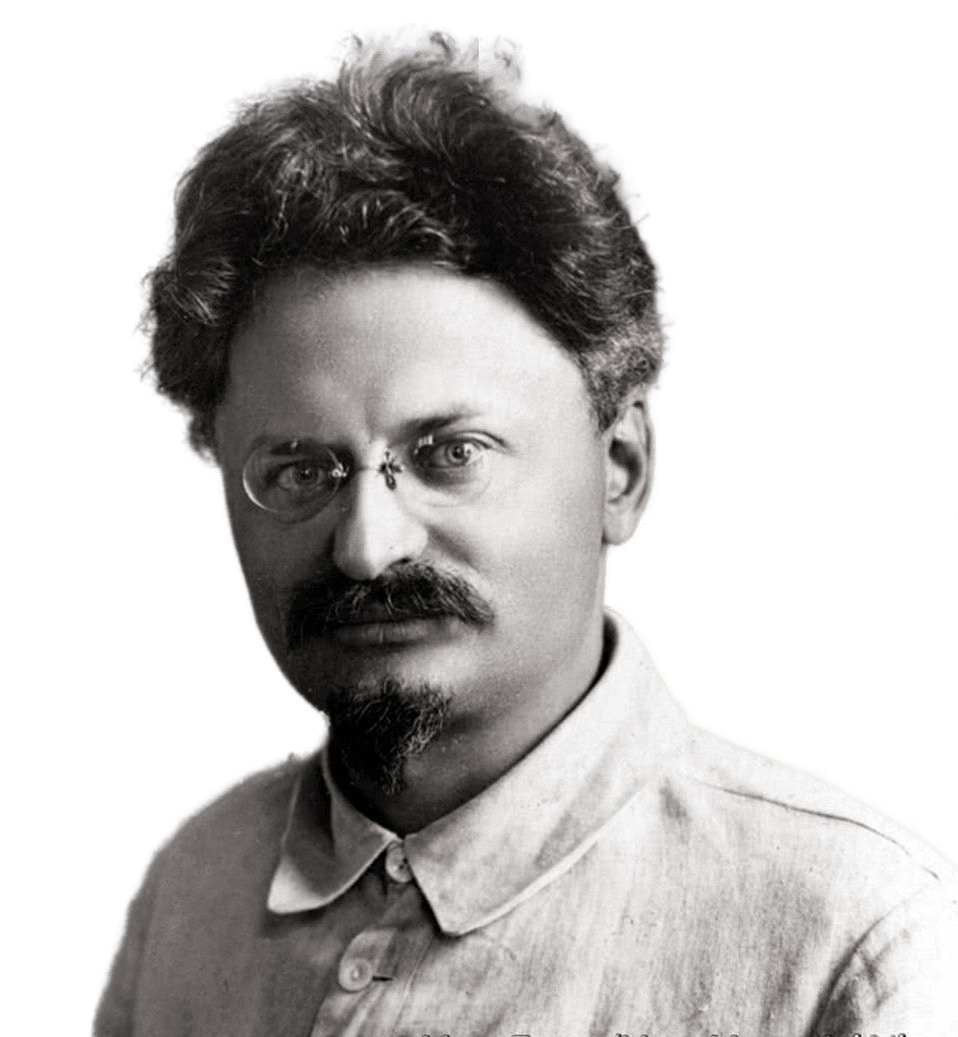

In the midst of the First Russian Revolution, in the fall of 1905, two men – the zealous revolutionary and Social Democrat Lev Trotsky and the young, successful solicitor general George Khrustalev-Nosar – met. This meeting determined the fate of one of them.

1905 – The Clash

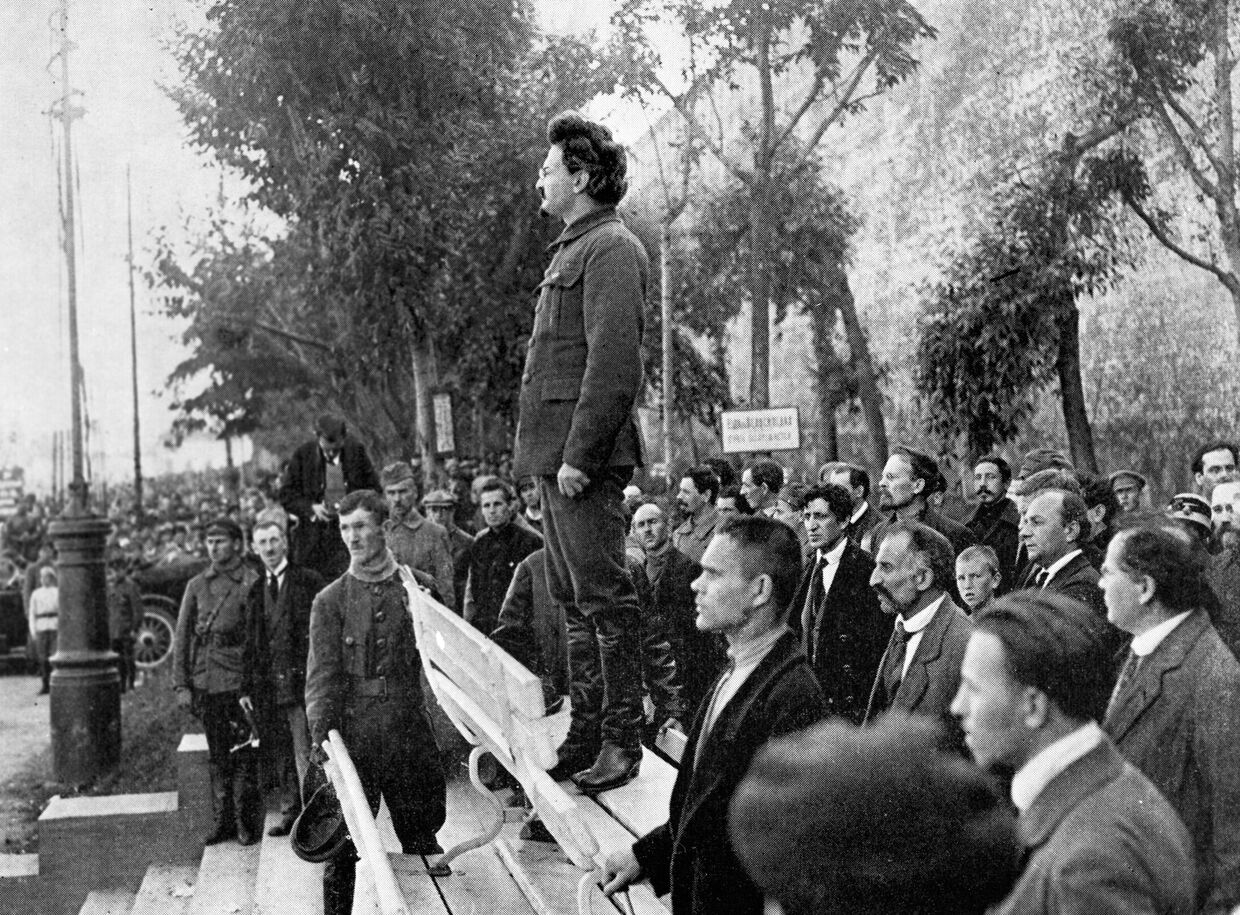

St. Petersburg, like the rest of Russia, was shaken by revolutionary unrest. On October 13, on the wave of a broad strike and strike movement of the proletariat, the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies was created. It was here that Georgy Stepanovich Khrustalev-Nosar, a native of Pereiaslav, Poltava province, and a sworn attorney for the workers, came to the forefront of history.

In his autobiographical essay in the 1920s, the well-known revolutionary N.V. Krylenko wrote about his role in the events of 1905 that on October 13, “Khrustalev-Nosary’s first speech with a proposal to form a Soviet of Workers’ Deputies took place “1. And the speaker’s proposal was apparently supported by the workers. Was it an accident? Not at all. Khrustalev-Nosar was already well-known: he had collected money for the families of the workers who had suffered after the shooting on “Bloody Sunday,” was detained by the police, was released, and had spoken at workers’ meetings and rallies. Not surprisingly, he was also the head of the Council. Khrustalev had no desire for bloodshed and believed that political freedoms in autocratic Russia could be established by gradual, reformist means.

In the same days, learning about the beginning of large-scale unrest in the Russian capital, Lev Trotsky, a social democrat with “baggage” of revolutionary experience, urgently arrived from Finland. He later recalled:

“I arrived in St. Petersburg at the height of the October strike. The strike wave was growing wider, but there was a danger that the movement, not covered by a mass organization, will disappear in vain.

2 Under the surname Yanovsky (Yanovka was the village where he was born and grew up) Trotsky infiltrated the executive committee of the St. Petersburg Soviet. He rushed to become the leader of the revolution in Russia. His attitude to the tsarist government was resolute and uncompromising: it must be wiped off the face of the earth.

The relationship between the leaders of the St. Petersburg Soviet was not straightforward. Jacob Wernström, who attended Council meetings, recounted: “Some speakers used too harsh expressions, such as comparing the autocracy with a hydra to be destroyed. Khrustalev stopped such people… “3 Trotsky, on the contrary, only welcomed such things. At a meeting of the Council in the Salt Camp at the end of October, its participants solemnly welcomed the old Narodnaya Volya, the terrorists Lev Deich and Vera Zasulich, released from prison at the height of the revolution. Trotsky said at the time: “As they waited for their release, so shall we wait for the overthrow of the autocracy … It will roar and die like a beast of prey

In the Council, the call for an armed uprising did not officially appear until November 27, after the arrest of Khrustalev-Nosar. After that, the members of the Council were arrested. In prison, differences of opinion emerged: Khrustalev-Nosar categorically refused to consider an armed uprising as a goal of the Soviet, although he did not object at the trial under pressure from his comrades. Apparently, it was then that his differences with Trotsky became apparent. They clearly had different views on the future of Russia, but both were sentenced to exile in Siberia.

1913 – Confrontation

Sent into exile in Obdorsk in 1907, Trotsky and Khrustalev-Nosar, however, stopped at a staging post in Berezov, where, back in the 18th century, an associate of Peter the Great, Alexander D. Menshikov, was exiled with his family for several years. From there Trotsky and Khrustalev managed in different ways to escape abroad. Trotsky in exile missed the revolutionary times, indicating in a March 1908 letter to fellow Soviet member D.F. Sverchkov:

“You cannot create a Council of Workers’ Dep[utates] today. We are living in an epoch of victorious counter-revolution, this is the basic fact. The Party at this moment is a sail that is not blown by the wind.”

Khrustalev-Nosar lived in Paris in the apartment of V.L. Burtsev, a well-known publisher, social revolutionary and provocateur expositor, and worked in his newspaper “Future” and in the editorial board of the Paris Herald. In 1909 he left the RSDLP and broke with Social Democracy. He was engaged in research in the field of labor and cooperative movement. He wrote in 1913 to his brother, Viktor, a student in St. Petersburg, that he was working on his memoirs, “My Life” and on a reflection of his experience of the events of 1905.

In the same year of 1913, the unbelievable happened. Khrustalev-Nosar, a long-time lawyer, was arrested by the Paris police… on suspicion of stealing watches, bed sheets and books from one Zimmerman! This case served as another reason to “expose” the entire revolutionary movement.

Lev Trotsky felt it his duty to “cleanse” fellow revolutionaries of the “dirt” poured on them by journalists because of the Khrustalev-Nosar case and wrote an exposé article. According to Trotsky, “Khrustalev shone a double light: the Party and the masses. But both lights were reflected, i.e., alien. “7 Lev Davidovich blamed Khrustalev for his break with the Social-Democrats. Trotsky concluded that the legend surrounding the personality of Khrustalev-Nosary had been created by the press, and the workers believed it.

After reading the issue of the newspaper “The Beam” with this article, Khrustalev-Nosar did not keep silent, considering Trotsky’s statements about his address a slander:

“We formed a council. Thanks to your adventurist speeches, it was crushed by reaction. The resolution you imposed on the council after my arrest [about the preparation of an armed uprising] was not only a grave political mistake, but also a provocative act”.

He believed that he enjoyed real authority among the capital’s proletariat. The former chairman of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies called on Trotsky to answer immediately for his words.

The latter was obviously furious and unleashed a new batch of criticism. In his article “To Eliminate the Legend,” he wrote: “Khrustalev gathered the last vestiges of his spiritual energy and frantically flailed about in an effort to make the former not the former. Khrustalev, in turn, in a letter dated April 26 to his brother Victor in St. Petersburg, wrote: “Trotsky could not hold out to settle accounts with me. A scoundrel and murderer from around the corner… How cruel and unfair life is to us.

February 1917 – On different sides of the barricades

The First World War, which began in August 1914, split the public. The First World War, which began in August 1914, divided the public. Trotsky belonged to those who remained in exile and wished Russia’s defeat from there: the war is not necessary to the masses, it is necessary to the government and the bourgeoisie. In one of his articles in 1915, he wrote: “The more mighty is the mobilization of the working people against the war, the more the experience of political defeat will be taken into account by the working class, the sooner it will become the driving force of the revolutionary movement.

Khrustalev-Nosar, on the contrary, sincerely eager to help his country in the war, arrived in Russia in the fall of 1915, but was immediately arrested. He hoped for a political amnesty to help in the fight against German spies, and wrote: “It is now, more than at any other time, that the legitimate activity of the authorities, of all its organs…. is required. Only in this way can one still think of raising the fighting power of the people and bringing the war to a victorious end. “12 In prison, he wrote a paper entitled “The Problem of Death,” in which he wondered, “Yes, and will there still be a social revolution itself…? What if the idea of permanent revolution is asserted by Parvus alone…?”

But the authorities did not hear the former chairman of the St. Petersburg Soviet and even sentenced him to three years of hard labor. Not even six months after the court decision, however, the revolution began. On a wave of release of political prisoners and Khrustalev-Nosar came out of the House of preliminary detention. This happened on February 27, 1917. Once again, as in 1905, the workers had asked him to be a “Soviet” leader, but time had passed. At the Tavrichesky Palace, Khrustalev encountered resistance from the Social-Democrats. Disappointed, he left for his small motherland, Pereyaslav, where, in the summer of 1917, under conditions of complete collapse, he founded the Pereyaslav “republic,” which did not last long.

Trotsky, meanwhile, returned to Petrograd. He became chairman of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.

October 1917 brought the Bolsheviks to power. How did Khrustalev-Nosar feel about this? In his book “From the Recent Past”, published in Pereyaslav in the summer of 1918, he wrote: “On the ruins of the former greatness and the former power of centuries, who were able to pray fervently, believe passionately and generously erect temples, reigned intoxicated by freedom, the Ilot14 and the Red Guard criminality… “15. In the preface to the book, he accused L.D. Trotsky of cooperating with the police and that he worked for the Germans during the war, engaging in espionage. Khrustalev-Nosar had no idea that the bloody denouement of his confrontation with the “Red Guard criminality” was, in fact, already close.

1919 – Finale

Khrustalev-Nosar, a veteran of the revolutionary movement, was arrested and shot by decision of the Bolshevik Revolutionary Committee in Pereyaslav in May 1919. We know that he actively fought with the Bolshevik organizations and with the committees of the poor. Old-timers recalled that the body of the executed Khrustalev-Nosar was later fished out in the Dnieper16. And the centurion of the Ukrainian army, Nikifor Avramenko, an employee of the Soviet military committee in Kanev in 1919, while in Polish exile, left memoirs in which he reported that a drunken Cheka officer Gabinsky had stolen a paper on which it was written:

“Top Secret. Comrade Gabinsky is instructed to liquidate an impostor, the chairman of the council in Pereyaslav, Khrustalev-Nosar, together with his closest collaborators. To act very cautiously and without publicity. People’s Commissar L. Trotsky.”

However, this testimony is most likely a fiction designed to discredit Trotsky. There was even a rumor that Trotsky had personally requested that Khrustalev’s alcoholized head be brought to Moscow as proof.

“The revolution devours its children,” said Georges Danton, a figure of the French Revolution before his execution. This is what ultimately happened not only to Khrustalev, but also to Trotsky. There are many differences in their fates, but also many similarities. Imbued with the ideas of humanism, solidarity, and respect for the people and the government, the European-thought enlightener George Khrustalev-Nosar was shot. He never published his memoirs, which he wanted to call “My Life”. Lev Trotsky, a social democrat, a participant in the overthrow of the “old regime”, built the Red Army, held important positions in Soviet Russia and believed in the world revolution. He published his autobiography, ironically, under the very title his opponent dreamed of. But fate turned away from him as well. In 1940, exile and oppositionist Trotsky was murdered by a Soviet agent in Mexico.