10.01.2023

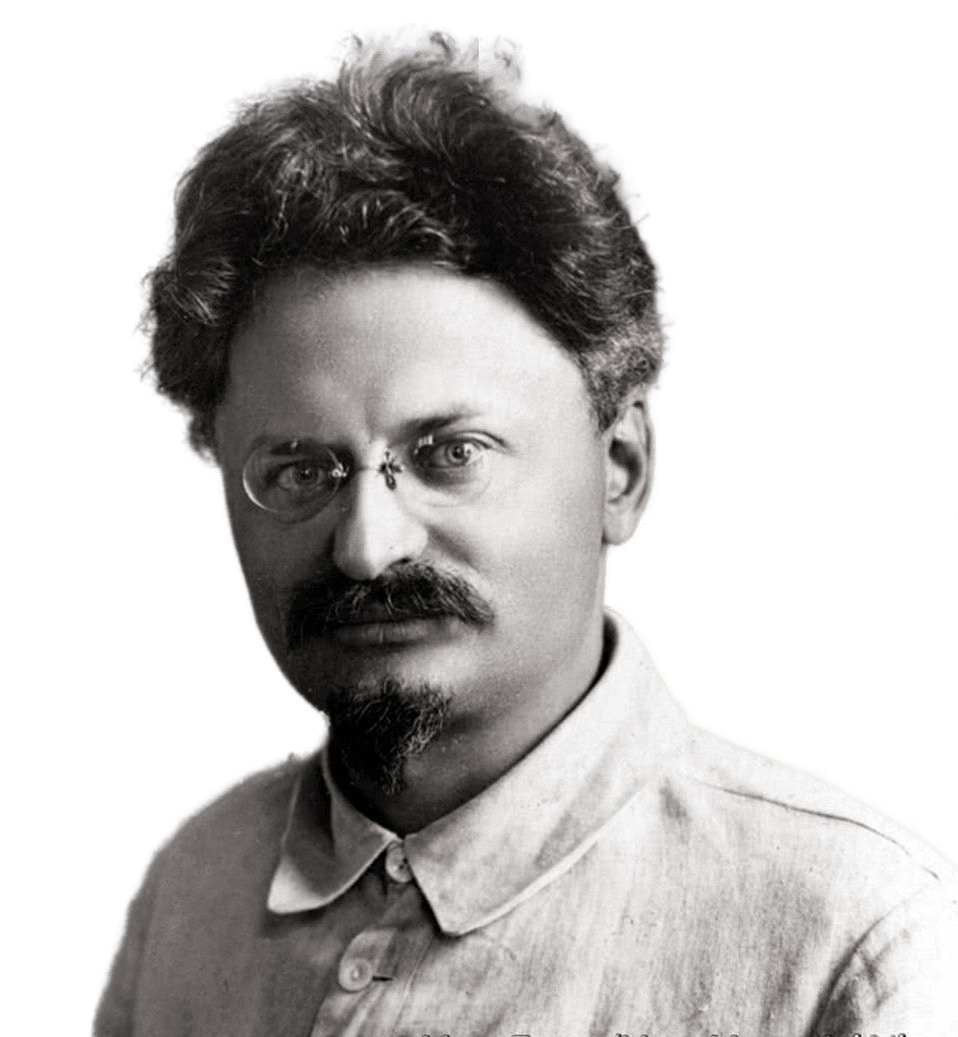

In the first post-revolutionary years, Soviet propaganda presented Leon Trotsky as a mythical hero, and later as a mythical villain.

But even today, when information about the life and work of the “second leader” of the October Revolution is available as much as possible, the myths surrounding him have not dissipated.

Myth One: Russophobe

The enemies of the revolution in Russia and abroad took full advantage of Trotsky’s Jewish heritage. He was accused of hating everything Russian, of persecuting the church, of subjugating the country to “world Zion. In the caricatures, a red-bearded baboon with a beard and pince-nez sat in the middle of the Kremlin on a pyramid of skulls. The self-appointed “master of Russia” was sarcastically mocked by Kuprin and Averchenko. The inhabitants of the Jewish settlements, who were slaughtered by the Whites and other atamans “for Trotsky,” had no time for laughter. One day a delegation of these unfortunates came to Moscow, seeking protection, but Lev Davidovich told them, “Tell those who sent you that I am not a Jew.

He really was far from the traditional Jewish life. He was born in the vast expanse of the Kherson steppe, where his father David Bronstein bought up 400 dessiatinas of land. The family spoke not Yiddish but Russian-Ukrainian surzhik, his father did not observe Jewish rituals and called himself “Davyd Leontevich” and gave his children Russian names – Alexander, Lev, and Olga.

In his memoirs, My Life, Trotsky wrote: “By the time I was born, my parents’ family already knew affluence. But it was the stern exuberance of people rising up from want… All muscles were tense, all thoughts were directed to labor and accumulation.” The children had no toys or books – literacy was taught to Lev by his uncle, the publisher Moses Spencer (father of the poetess Vera Inber). He was the first to notice the boy’s abilities and insisted that he be sent to St. Paul’s Gymnasium in Odessa. There Lev received an excellent education, learned four languages and was infected with revolutionary ideas, for which he left the first year of university and took a job at a shipyard in Nikolaev, to agitate the workers. The same was done by the midwife Alexandra Sokolovskaya, who later became Lev’s wife and gave birth to his daughters Zinaida and Nina.

In 1898 the young agitator was first arrested and spent two years in a prison in Odessa. There he was impressed by the warden Nikolai Trotsky, who held in obedience a thousand prisoners, other wardens, and even the prison governor. All subsequent life Lev used his methods, and after his escape from exile, he inscribed the name “Trotsky” in his fake passport. He left his wife and children in Siberia, and in Paris, intoxicated with freedom, became infatuated with the young revolutionary Natalia Sedova. Becoming his common-law wife (Sokolovskaya stubbornly refused to grant a divorce), she gave birth to two sons – Lev and Sergei.

A Russian wife, the Russian language and Russian literature did not make Trotsky Russian, but it made him even less of a Jew. Believing in Marx’s postulate that “workers have no fatherland,” he harbored neither love nor hatred for any nation, seeing them all as material for the world revolution, in which he firmly believed.

Myth two: the true Bolshevik

Glorifying Trotsky as the leader of the revolution, propagandists concealed, and sometimes did not know, that he only joined the Bolsheviks in 1917. On learning of this, his friend Adolf Joffe exclaimed: “Lev Davidovich! They are political bandits!” He replied, “Yes, I know, but the Bolsheviks are the only real political force now.”

Prior to this, Trotsky’s relations with the Bolsheviks had been, to put it mildly, difficult. At first the young Marxist fervently supported Lenin against his opponents, earning him the nickname “Lenin’s baton.” But already at the Second Party Congress in 1903, he defected to the Mensheviks. A war broke out between him and Lenin in the press: Trotsky called his opponent a “brisk statistician” and a “slovenly lawyer,” the latter called him Balalaikin, after the character of Saltykov-Shchedrin, and later even Judushka – though in a private letter, exposed only in Stalinist times. It was then that the film “Lenin in October” put the epithet “political prostitute” in the leader’s mouth, which was permanently glued to Trotsky. In fact, Lenin referred to Kautsky in this way, but he had worse words for Leo Davidovich.

In 1904, Trotsky became close to the German-Russian socialist Alexander Parvus. This “elephant with the head of Socrates” won him over with his talent as a publicist and a depth of theoretical thought that Trotsky himself never had. Like Lenin, he willingly borrowed ideas from the “elephant,” such as “permanent revolution. In the revolutionary year of 1905, he and Parvus appeared in Petrograd and took control of the city council of workers’ deputies. They already imagined taking over the capital, but at the end of the year the council was disbanded, and Trotsky was thrown into the “Kresty”. After sitting there for more than a year, he was sentenced to perpetual exile in Obdorsk (now Salekhard). Not getting there, he escaped, traveling 700 kilometers on a reindeer with a drunken musher, whom he slapped on the cheeks every now and then, so that he would not fall asleep.

During the First World War he was whisked all over Europe and even to America, where he admired New York – “the city of the future” – and was going to stay for a long time. The February Revolution changed plans: Trotsky rushed to Russia, but was detained in the port of Halifax as a German spy. To its misfortune, the Provisional Government asked for the release of the “honored revolutionary,” and on May 4 – a month later than Lenin – Trotsky arrived in Petrograd.

He created a small faction of inter-regionalists in the capital’s council, which he soon “presented” to the Bolsheviks. And he did not fail: after a little time in the same “Kresty” after the July mutiny, he was released and became chairman of the council. Soon he formed the Military Revolutionary Committee to prepare an uprising and was able to release the energy he had been accumulating for a long time. Driving around in a car to military units, with incoherent, but ardent speeches he persuaded them to side with the Bolsheviks: “You, bourgeois, have two coats – give one to a soldier. Do you have warm boots? Stay at home. The worker needs your boots!” These speeches sent the listeners into ecstasies, and sometimes the speaker himself fainted.

He also collapsed on the night of October 25, when the Winter Palace was taken – before that he had not slept for two nights and had hardly eaten. On the 26th he addressed the Second Congress of Soviets, suggesting that the former allies, the Mensheviks, “go to the dustbin of history. On the 29th, right from the meeting of the Petrosoviet, he went to the Pulkovo heights, which were being approached by Krasnov’s Cossacks. Another fervent speech – and the Cossacks retreated without a fight.

In the new government Trotsky received the post of People’s Commissar (he invented this name) for foreign affairs. He also invented another expression – “red terror,” which he promised to apply to all those who disagree: “Our enemies will be waiting for the guillotine, not just prison. But for now, the main thing was to make peace with Germany, which the People’s Commissar approached in a peculiar way. At the talks in Brest-Litovsk he offered “peace without any conditions,” and when he received a refusal, he tried to agitate the Kaiser soldiers. Having lost patience, the Germans went on the offensive in February 1918 and threatened Petrograd. Lenin had to twist his comrades’ arms, persuading them to accept the hardest terms of peace. A reprobate Trotsky supported him, but was removed from foreign affairs. In March he was given the key new post of People’s Commissar for Military Affairs – everyone understood his indispensability.

In spite of this, many Bolsheviks did not accept Trotsky. Remembering Lenin’s denunciations, he was considered an upstart, a poser, an adventurer, accused – quite rightly – of ignorance of people’s life and indifference to it. They pointed to his “bourgeois” habits, his love of Havana cigars and French novels. Lenin himself, no longer scolding Trotsky publicly, was always mindful of his “Malyshevism.

Others also remembered this when the pedestal of the leader, which Lev Davidovich considered his by right, wobbled beneath him.

Myth three: the commander

Trotsky’s main merit his supporters considered the creation of the Red Army and the organization of victory in the Civil War. But the merit was different: he was the first to realize that the Bolshevik slogan of a “people’s army” with elected commanders was good for overthrowing power, not for defending it. When in the summer of 1918 the rebellious Czechoslovaks, together with the Whites, overthrew Soviet power from Penza to Vladivostok, Trotsky demanded “the cruelest dictatorship”. First by car, then by personal armored train, he moved from one front to another, restoring discipline by the harshest measures – up to the execution of every tenth according to the ancient Roman model. He insisted on a single uniform; he himself, along with the senior command staff, wore a black leather jacket.

The People’s Commissar General, who had never served a day in the army, recruited former czarist officers. Their families were threatened with hostage-taking so they would not run away to the enemy. By carrot and stick almost half of the officer corps was lured into the Red Army, which to a large extent won the victory.

Lenin supported the involvement of “military specialists,” but Stalin opposed it, which led to his first clash with Trotsky. At first it seemed that the little-known Caucasian, who did not shine with his oratorical gift, had no chance against the world-famous “demon of the revolution. Lev Davidovich considered his leadership of the party a done deal, not allowing even the idea that Stalin – this “outstanding mediocrity” – could overtake him. But he, an experienced chess player, played the game like clockwork. First, he lured to his side the majority of the Politburo members, frightened by Trotsky’s dictatorial ambitions. Then he surrounded the sick Lenin with attention, constantly visiting him in Gorki (Trotsky had never been there). When Ilyich died, Stalin did everything to prevent his rival from attending the funeral, and appeared in the eyes of the people the chief heir of the leader. Then he quietly “shoved” Trotsky’s supporters in the Party apparatus and the army. Feeling something wrong, he asked to be sent to Germany as a “common soldier of the revolution. The Politburo refused, and in January 1925 removed him from his post as People’s Commissar, making him chairman of the unimportant Electrotechnical Committee.

Trotsky came to his senses in the fall of 1926, when he was kicked out of the Politburo, but his attempts to protest were doomed. Trotsky was expelled from the Party, exiled to Alma-Ata, and in 1929, he was completely expelled from the Soviet Union and had to be carried out of his apartment in his arms because he refused to leave the country.

He lost his duel with Stalin cleanly, showing himself to be an even worse strategist than in military operations.

Myth Four: The conspirator

At public trials in Moscow, prominent Bolsheviks Pyatakov, Sokolnikov, and Serebryakov repented that on Trotsky’s orders they had engaged in sabotage – breaking machine tools, poisoning food, delaying the construction of giants of industry. Trotsky’s worst enemy, Nikolai Bukharin, described secret negotiations with him, in which Lev Davidovich allegedly admitted that he had entered into a deal with the German General Staff, offering the Germans, simultaneously with their attack on the USSR, to raise an uprising, promising them Ukraine for help, and the Japanese – the Far East.

Not content with this, he was also attributed a connection with British intelligence; Vyshinsky, the chief prosecutor, declared, “The whole bloc, headed by Trotsky, consisted of nothing but foreign spies and tsarist guards. For all the absurdity of the accusations, Trotsky took them hard: not only was he afraid that the Soviet workers would believe them (and indeed they did), but he resented that he was being attributed to collusion with the Nazis. The commission he put together found a lot of inconsistencies in the Moscow trials, but no one in the Soviet Union knew about it. By that time, Article 58-1, “counterrevolutionary Trotskyist activity” became a verdict for hundreds of thousands of people.

It came to Lev Davidovich. On August 20, 1940, Ramon Mercader, a 27-year-old Spaniard, was sent to him under the guise of an admirer. He brought his article to Trotsky and while he was reading it, he broke his skull with an ice-axe. The frustrated leader of the world revolution died the next day.

Myth Five: The Savior

When, after many years of silence, Trotsky was remembered again in the homeland, an opinion was reinforced: his coming to power would have saved Russia from many of the troubles it had experienced under Stalin. But this is another myth. And mass terror, and forced collectivization, and strict control over the private life of citizens – all this was first proposed by Lev Davidovich, and Joseph Vissarionovich only put his ideas into practice with the ruthlessness and methodology, for which the “demon of the revolution” was incapable.